The world of Arabs (the WoA), as a distinctive part of the globe, is of extreme significance for both global politics and the global economy. On the other hand, this region is featured by slow democratic development, political instability, religious extremism (Islamic fundamentalism), and many reasons for long-time inter-ethnic conflicts especially on the Israeli-Arab relations and regional insecurity. It is quite obvious that the WoA needs comprehensive political, social, and economic reforms which the Arab Spring’s protesters clearly requested in 2010−2013. The crucial issues of reforms are about national development and governance, a succession of political authority, removal of political authoritarianism, and Arab relations with Israel and the USA.

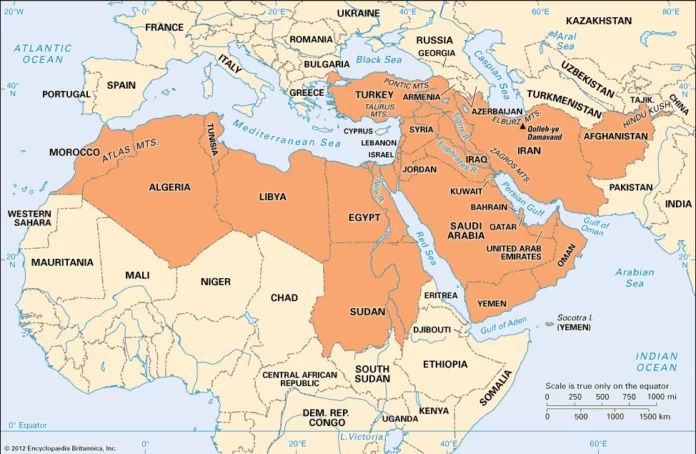

The WoA is composed politically of 22 member states of the Arab League Organization (officially, The League of Arab States) including those from the regions of the Middle East and North Africa (the MENA), and connected by numerous bilateral and multilateral conventions and agreements. On the one hand, those 22 member states are different in size, governmental form, and richness of natural resources, but on the other hand, all of them possess many common attributes that are culturally, confessionally, and ethnically unifying them: language, alphabet, religion, history, customs, values, and traditions.

The Arab League Organization

This league seeks to promote political, cultural, and economic cooperation between its 22 member states (including representatives of Palestine from the PLO) on two continents. It was founded in 1945 by six founding Arab states: Iraq, Egypt, Transjordan (today Jordan), Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. One of the first and focal political acts by the league was an economic boycott of Zionist Israel from its proclamation in 1948 until the Oslo Accords in 1993. However, its attempt to present a united political (Arab) platform on some broader issues followed by harmonious economic cooperation is up to now limited usually due to American interference in Arab affairs. Nevertheless, such failure as well as is a result of the way of functioning of the Arab League Organization as its decisions are binding only for the member states that voted for them. Internal factors, in addition, like a form of state (monarchy or republic) have influenced Arab states’ disagreeing policies.

External relations, as well, are historically and currently dividing Arab nations within the league. For instance, during the Cold War 1.0, they supported different sides either the USA or the USSR. Contemporarily, the nature of their relations with different external actors (Russia, China, USA) directly determined the political and economic actions by the member states of the Arab League Organization that were visible, for instance, in the cases of two Gulf Wars or the Arab Spring in 2010−2013. In 2011, the Arab League Organization condemned Libya’s leader Muammar Gadaffi’s human rights abuses and called for the imposition of a no-fly zone over Libya in an unprecedented request for UNSC intervention.

The historical context

Most of the world of Arabs for some four centuries consisted of provinces under the Ottoman Empire (Sultanate). The first half of the 16th century experienced a great power advance of the three crucial Islamic empires at that time: the Ottoman Empire on three continents, the Safavid Empire in Persia, and the Mughal Empire in India. In the middle of the same century, these three Islamic states controlled a broad portion of territory and seas from Morocco, Austria, and Ethiopia to Central Asia, the Himalayas, and the Bay of Bengal. Much of Central Asia was in the possession of another Turkish dynasty – the Uzbek Shaybanids, whose capital was in Bukhara. Khanates with Muslim rulers existed in the Crimea and on the Volga River at Kazan and Astrakhan. All these states have been established by Turkish-speaking Muslim dynasties with an extreme military feature. All except the Safavid Empire in Persia were of Sunni Islam, but the Safavids, however, followed Shia Islam. This historical fact encouraged sharp antagonism, rivalry, and warfare in which the Middle Eastern Arabs have been involved. Up to 1639, a majority of the Arabs became governed by the Ottoman Sultans.

By the death of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror in 1481, the Ottoman Turks conquered the Byzantine capital Constantinople, and the biggest portions of the Balkans. Thereafter, the sudden revival of Islamic Persia under the ruler Ismail I (1500−1524) pushed them back to the western part of the Middle East. However, Ismail of Persia was defeated in 1514, and Syria and Egypt have been conquered in 1516−1517 by the Ottomans. From that time onward, the Ottoman Empire was indisputably the greatest Muslim state of the time. In around 1530, the Ottoman subjects numbered around 14 million compared to England which had 2.5 million, or Spain 5 million. To the European observers of a different kind, the power of the Ottoman Turks followed by the strength and discipline of the Ottoman army were matters of admiration and respectful concern.

The end of the Ottoman Empire after WWI should have resulted in the independence and self-governance of the Arab people. However, the provisions of the secret British-French Sykes-Picot Agreement (May 16th, 1916) between Foreign Ministers of the UK and France, divided and kept most of the WoA under their imperial rule. Two decades after WWII, some parts of the WoA are still fighting against colonial domination by the West. For instance, French colonialism finished in 1946 in Lebanon and Syria, in 1956 in Morocco and Tunisia, and in 1962 in Algeria. Differently to France, however, the Bretons at the same time after WWII sought, by all means, to extend their colonial power in the Middle East by signing treaties and making connections with loyal Arab local rulers.

Nevertheless, the impact of the Western colonial legacy on the new Arab countries is enduring at least for the next focal reasons:

- The Western colonial order established traditional systems of administration with absolute family rule in the majority of colonial-ruled Arab communities. Over time, the colonists offered their loyal Arab regimes financial, military, and technological support.

- The political authority and territorial-administrative border have been marked, recognized, and institutionalized in order to protect the present situation. Nevertheless, what was created and maintained as political entities by the French and the Bretons was not for the reason of coherence and economic functioning nor because of historical reasons but, primarily, to satisfy their colonial-imperial interests.

- The legacy of the British colonial rule of Palestine (the Mandate), from the 1917 Balfour Declaration to the British withdrawal in 1948, not only failed to integrate or harmonize the wishes of Judeo-Jewish and Arab Palestinian communities but, contrary intensified the differences to be one of the most bloody conflicts in the post-WWII history up to our days (The 2023−2024 Gazan War, Israeli aggression on South Lebanon in 2024).

- Political anti-colonial opposition groups started to be formed in the Arab Middle East and North Africa between two world wars and originally had the aims of resisting foreign colonial power and administration and gathering the Arabs to support their own political independence. The opposition movements later fought for the system’s reforms of Government and demanded benefits for the working class and those coming from the poor social strata.

- A social stratum has been created and grew increasingly large as the process of modernization followed by oil revenues gradually transformed the societies of the MENA. The new working class became directed against both foreign (Western) occupants and their capital of exploitation. It became a national struggle and attracted those Arabs who had been marginalized within their societies. Step by step, the opposition political groups, parties, and movements within the WoA attracted socialists, Islamists, communists, and nationalists for the realization of their political and national tasks.

Therefore, the historical context of the Arab position in the contemporary Middle East is crucial for an objective understanding of current tensions and wars, but as well as for bridging a historical gap of values between the WoA and the West. Foreign (Western) involvement and occupation of Arab provinces in the Middle East, nevertheless, did not end with independence. The most troubling problem pondered by Arabs today is the burdensome, humiliating fact that the Arab region is the only part of the world where foreign armies today still invade and occupy the Arab lands. However, present Western claims of advocacy of democracy and freedom are deeply mixed with the images of historical Western colonial domination and occupation in the contemporary Arab collective memories.

The second Gulf War in 2003, or the Western military invasion of Iraq, well illustrated how the problems of the region of the Arab Middle East very often are to be transformed into a state of greater regional complexity and broader international significance. However, instead of progress toward solutions to the current problems, the Arabs appeared to be involved in a situation of total insecurity and administrative-institutional incapacity.

On one hand, while reforms are a common wish in the Arab countries, it is, on the other hand, unclear how to break out old undemocratic political models of governmental administration, and how to develop and encourage competent, ethical, and accountable systems of governance in the majority of the MENA countries as it was clearly put on agenda during the Arab Spring in 2010−2013. Besides, no less challenging for the Arabs is to be able to lead effectively within a new reality in global politics and international relations where „pre-emption“ with armed forces and „threatening diplomacy“ are increasingly becoming the methods of choice for conflict resolution.

The Arab Spring (December 17th, 2010−October 26th, 2013)

The Arab Spring started in mid-December 2010 in Tunisia and in the spring of next year, people’s demonstrations brought an end to the regime of Tunisian autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali which lasted for 23 years. The Tunisian protests started because Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire when he could no longer pay police bribes. However, those political and pro-democratic events in Tunisia immediately inspired protests against similar authoritarian regimes in the MENA region like in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Iraq, Jordan, Bahrain, and Oman. Nevertheless, while on one hand Arab protests fastly spread out from one state to another in the region, on the other hand, general regime change across the Arab MENA did not come as quickly as it was in the case of Tunisia.

During the Arab Spring and up to the present, there are thousands of protesters in the MENA region who are tortured, imprisoned, or sentenced to the death penalty. The Arab Spring continued in Syria, Yemen, and Libya up to now in the form of a prolonged civil war in which different groups of Islamic fundamentalists took participation. As the Arab Spring in some Arab countries became transformed into a long and devastating civil war, the initial optimism by the international community to the protests of 2010−2013 which have been understood as a democratic cross-regional movement, became gradually pessimistic.

It has to be noticed that the Arab states that have been hit by the Arab Spring (revolution and counter-revolution) are sharing a lot of common features. Their unique politics of inner affairs and international relations shaped their contemporary histories. As a common feature of the Arab Spring was the fact that the street protesters had in common a rejection of dictatorial regimes and a desire for both constitutional and representative governmental administration. However, some crucial differences between Arab countries existed too. Therefore, there are three crucial themes to be particularly presented in order to properly understand the state of turmoil in which the MENA region found itself during the time of the Arab Spring: 1) Economic failure, 2) State repression, and 3) Geopolitical context.

Some of the focal features of the Arab Spring can be summarized as follows:

- Poor long-term economic growth across the MENA region surely contributed a lot to people’s dissatisfaction with the economic situation. In general, the economic growth of the world of Arabs is during the last half of the century negative and, consequently, rates of unemployment, underemployment, and poverty were among the highest in the world in 2010 on the eve of the Arab Spring. Social inequalities increased followed by the corruption and the practices of clientelism of ruling classes. The incident in Tunisia in mid-December 2010 with Mohamed Bouazizi clearly stressed the Arab Spring’s economic and political dimensions.

- The Arabs who took the street had the aim to secure democratic freedoms and to crucially improve the accountability of their Governments and Presidents/Kings (the executive powers). However, at the same time, they required the recognition of their human and political rights as citizens followed by protection from repression at the hands of the state and its corrupted institutions.

- The international dimension of the Arab Spring is differently presented by different types of academic researchers and actors in international relations. On one hand, many regional orientalists claim that the (Arab) people of the MENA region (North Africa and the Middle East) are simply ungovernable and, therefore, they deserve autocratic rule, but the other experts emphasize that external actors share responsibility for ill-targeted economic policies and hard-line state repression. It is, for instance, well-known the negative influence of the IMF policies on Arab employment results or that the promotion of export economies by Western external actors (the EU) actively shaped the economic policies of the Arab nations.

- External factors in addition to having a strong impact on shaping the economy of the world of Arabs, they, as well as, supported the regional autocratic regimes from the Cold War 1.0 onward. However, the essence of the Arab Spring was that external factors continued to do so when demonstrations and uprisings started. Western external actors hesitated to express clear support for the protesters for the reason of their concerns for stability, prioritization of anti-terrorism and anti-Islamic radicalism policies, and consideration of their bilateral relations with a Zionist Israel. Even the Arab Governments of Saudi Arabia and Qatar, or regional Iran, had a strong influence on the outcomes of the Arab Spring by supporting existing political authorities or certain military-political organizations (ex., Hamas and Hezbollah).

Ex-University Professor

Vilnius, Lithuania

Research Fellow at the Center for Geostrategic Studies

Belgrade, Serbia

www.geostrategy.rs

sotirovic1967@gmail.com

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2024

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.