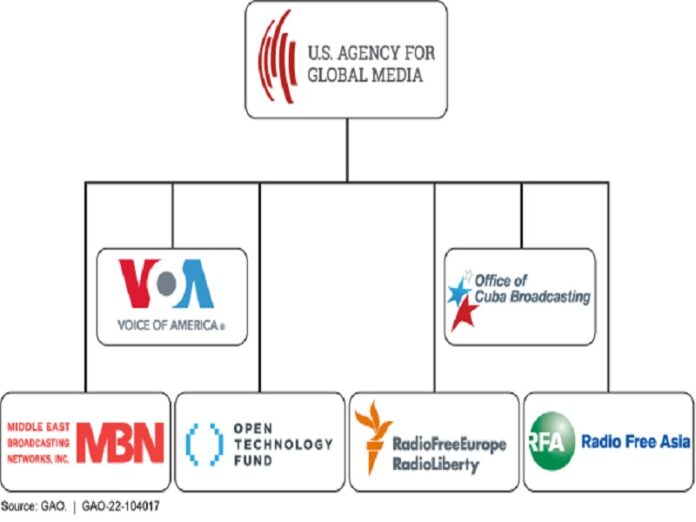

Trump’s Executive Order last week eliminating the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM), the rationale of which was explained here as regards to stopping the state’s funding of ideologically radical propaganda, has been condemned by critics as a deathblow to American soft power. That body is responsible for Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and Radio Free Asia, among several other foreign-focused outlets. It’s therefore understandable why some are concerned about the consequences.

The reality though is that their operations will probably resume after some time, albeit through what’ll likely be public-private partnerships abroad instead of purely state-run enterprises inside the US, and only with like-minded partners that share Trump 2.0’s populist-nationalist worldview. To elaborate, the $950 million that the USAGM requested for this year could be put to more effective use funding foreign experts, influencers, media, etc. who are from the places whose public the US wants to influence.

That was already happening through USAID, which is also being gutted and transformed as was explained here in early February, so it’ll either return to its original focus on physical development projects or divide information warfare responsibilities with whatever remains of USAGM. In any case, the point is that USAGM’s influence operations and USAID’s more direct meddling ones are expected to be less centralized than before and outsourced to a much greater degree as a result of Trump 2.0’s reforms.

They’ll also be optimized by replacing their ideologically radical agenda with his team’s much more pragmatic one, which resonates with a much wider audience, and relying a lot more on informed figures abroad who have a better sense of the local pulse than DC-based bureaucrats do. The end result is that American soft power will be less visibly connected to the US, more effectively fine-tuned for targeted audiences, and promoted by what can be described as many more “agents of influence” than before.

It’s this final point that captures the essence of Trump’s reforms. As a successful businessman, Trump appreciates the free market, ergo why he envisages liberating the so-called “marketplace of ideas” from what he considers to be USAID and USAGM’s overbearing influence. Instead of keeping that marketplace “unfree” by letting them continue dictating editorial preferences, he wants to reduce their roles mostly to funding and supervising like-minded foreign contractors who’ll then function as “agents of influence”.

The problem though is that their host countries could replicate the US’ FARA like Georgia recently did to identify which broadcasters, influencers, media, etc. are receiving foreign funding and then obligate them to inform their audience of this so that they can keep it in mind when consuming their content. Additional responsibilities could also be mandated to make such arrangements too onerous for many to agree to, such as regular and detailed reporting of their activities, thus hamstringing this plan.

It’s here where the Georgian precedent is one again relevant since this example shows how aggressively the US will push back against even friendly governments that use the US’ own FARA as the model for their respective foreign agents legislation. Of course, it goes without saying that such a reaction strongly suggests that America is indeed guilty of intending to clandestinely fund foreign figures for influencing their societies, but not all targeted governments are as strong as Georgia’s to resist this pressure.

Moreover, USAID and USAGM’s ties to the CIA can lead to their successors indirectly funneling money to these same figures to help them evade scrutiny if they live in countries that have their own version of FARA, which can occur via crowdfunding as well as ad revenue from US platforms like YouTube and X. Governments could legislate that crowdfunding sites restrict foreign donations for their nationals if they want to still operate in their jurisdiction, however, and produce the names of donors upon court order.

By contrast, cracking down on US funding that might be indirectly funneled to foreign figures by the CIA via YouTube and X ad revenue at USAID and/or USAGM’s behest is more difficult, with the only realistic option being to legally treat all influencers above a certain number of followers as foreign agents. Under those circumstances, the US might encourage its “agents of influence” to flee abroad on the pretext that this infringes on their freedoms, after which they’ll continue producing their content with impunity.

The aforesaid pretext might be sufficient for the targeted audience not to negatively judge the figures who leave to avoid complying with their government’s FARA-like legislation, thus ensuring that they still retain most of their supporters despite living abroad and therefore saving the influence operation. In that case, it wouldn’t matter if the authorities requested that YouTube or X ban those figures’ accounts from being accessed within their jurisdiction since their audience could then just use free VPNs instead.

By hook or by crook, the US’ “agents of influence” – some of whom might even operate as such without their knowledge if the CIA indirectly funnels funds to them via YouTube or X to financially incentivize them to continue creating their content – are expected to expand their audience and sway. American soft power operations in this new era that’ll likely follow USAID and USAGM’s far-reaching reforms under Trump 2.0 will therefore be more creative, appealing, and effective than all that came before.