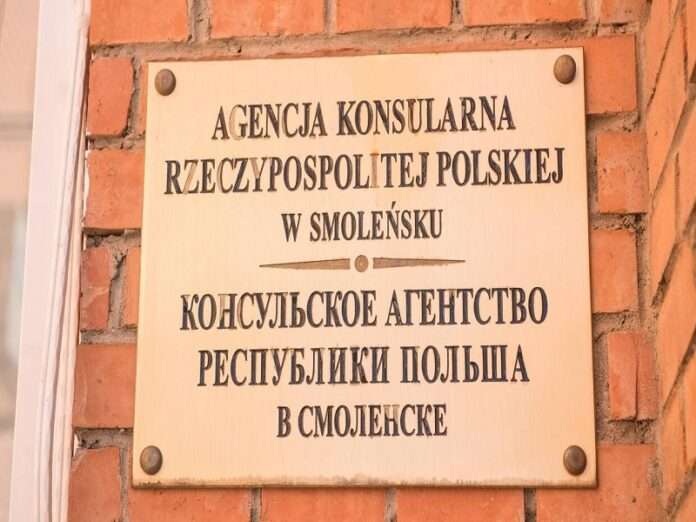

Russia finally responded to Poland’s spree of diplomatic provocations in recent months by shuttering that country’s consular agency in Smolensk. This wounds Warsaw’s pride since that facility looks after the memorials that were erected to the victims of the World War II-era Katyn killings and those Polish officials who lost their lives during the 2010 airplane tragedy that wiped out much of its leadership. Each holds a special place in Poles’ hearts and historical memory to this day.

It’s unlikely that those memorials will fall into complete disrepair as a result of this development, but it still unsettles many of its citizens, which was the point. The psychological warfare that their country has waged against Russia since the start of its special operation is now being responded to in a manner that affects practically every Pole. Nothing of tangible significance will change on the ground, but their imaginations will predictably run wild thinking about what might happen to these memorials.

Generally speaking and acknowledging the existence of exceptions, the Polish psyche tends to be very sensitive, especially concerning major events in their history. The 123-year-long partition made many of them forever suspicious of their much larger neighbors, which nowadays manifests itself in an arguably pathological paranoia of anything to do with Russia. Accordingly, plenty of Poles are thus likely to torment themselves needlessly worrying about these memorials due to their distrust of the Kremlin.

Shuttering the Polish consular agency in Smolensk therefore had a much greater psychological effect than if the actual Polish Consulates in Irkutsk, Kaliningrad, and/or St. Petersburg were closed in its place. It also avoided falling into the trap of being the first to cut off ties despite there already being more than enough legitimate grounds to do so if Moscow wanted and thus playing into the Polish ruling party’s victimization narrative.

Even though this is a reasonable and pretty mild response to Poland’s recent spree of diplomatic provocations, that country’s ruling party is still spinning it as an “aggressive diplomatic action” in the words of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. This was foreseeable since the authorities are exploiting many of their people’s paranoia of Russia as one of the primary platforms of their re-election campaign ahead of fall’s vote in the face of the rising challenge posed to them by the opposition.

For as much as this development unsettles plenty of Poles, however, it remains to be seen whether they’ll rally around the ruling party because of it. In fact, opportunistically and very shamelessly taking advantage of their feelings about this to that end might even end up backfiring if the opposition calls them out for doing so. Nevertheless, it should be taken for granted that Russian-Polish relations will continue to deteriorate since Warsaw likely won’t leave Moscow’s latest move unanswered.