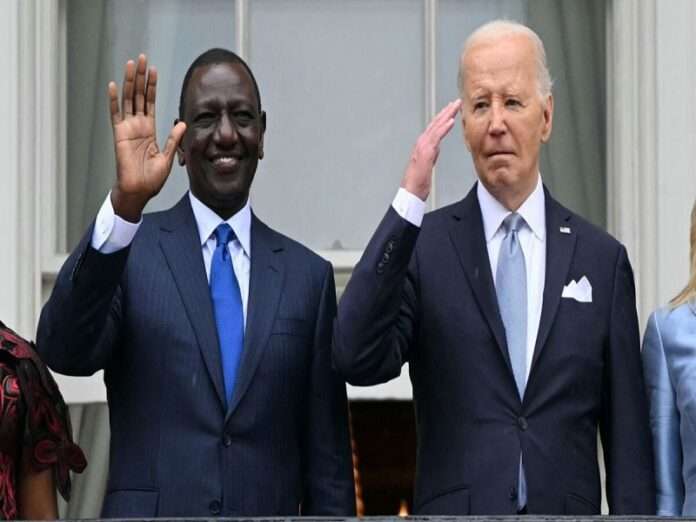

Kenya just became the US’ first sub-Saharan Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA), which will strengthen their strategic military relations and unlock plenty of flexible financing options for advanced weaponry. President William Ruto celebrated this development during his trip to DC last week to meet with his American counterpart, which was the first such visit by any African leader in over 15 years. This sequence of events was predictable for astute observers since Kenya regularly toes the US line.

It’s been like this ever since the Old Cold War, and while Kenya participates in China’s Belt & Road Initiative and hasn’t sanctioned Russia, it’s still considered much more of a pro-Western country than a multipolar one. This is proven by it hosting US military forces and voting against Russia at the UN. While others have been able to multi-align between the US-led West’s Golden Billion and the Sino–Russo Entente in similar circumstances, Kenya drifts a lot more towards the former in the New Cold War.

This hasn’t entirely been to Kenya’s detriment, however, unlike what many in the Alt-Media Community might instinctively be inclined to assume. The country has remained stable on the security front except for occasional Al Shabaab raids from neighboring Somalia and election season rioting. It’s also the best-performing economy in the region and among the top anywhere on the continent that is dependent on resource exports. These factors combined to predispose Kenya to continue along its pro-Western path.

The practical consequence of Kenya becoming a MNNA is that it’s now poised to play the role of the US’ proxy policeman in Global South states like Haiti, where its law enforcement officials and troops are expected to soon intervene to maintain law and order with American military backing. It goes without saying that Kenya would therefore do the same closer to home in Africa too if the US requests, thus enabling the latter to somewhat share the “burden of leadership” as its officials describe it.

Not only that, but Kenya might also become a central hub for the western part of the US’ Indo-Pacific strategy. Stockpiles could be stored there and drones possibly flown to neighboring countries like Somalia or nearby ones like the resource-rich but conflict-beleaguered Democratic Republic of the Congo. In this way, the US could rely upon this coastal country along the Afro-Eurasian Rimland to simultaneously exert mainland and maritime influence across this broad swath of space.

Observers can expect Kenya’s political hostility towards Russia to intensify as American influence increases. Kenya already compared Russia’s special operation to a colonial war, condemned Russia’s withdrawal from the grain deal as a “stab in the back”, and even recently criticized its pragmatic approach towards North Korea at the UNSC. Nevertheless, economic and political ties with China still remain solid, but their future can’t be taken for granted if the US forces a zero-sum choice upon Kenya.

Unless Kenya’s impending pro-US pivot makes life more difficult for a significant amount of its population, then there isn’t expected to be much pushback against this policy since most folks there are more concerned with daily matters in their own lives than with geopolitical affairs. The US’ goal is therefore to ensure that there aren’t any serious disruptions to everyday life in the event that Kenya’s relations with Russia worsen and its ones with China eventually become troubled.

It’ll also keep a watchful eye on domestic political processes to ensure that pro-US politicians remain in power and aren’t democratically ousted by multipolar members of the opposition. With these likely consequences of its MNNA designation in mind, it can be concluded that Kenya voluntarily subordinated itself to becoming the US’ latest client state. The quid pro quo is that Kenya will be the US’ policeman in parts of the Global South in exchange for more Western investment and political support.