The Taliban’s Ministry of Border and Tribal Affairs posted on X over the weekend that it’s studying the Wakhan Corridor, which is described as bordering both Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) and Pakistan on the south along what was also characterized as the “hypothetical” Durand Line. That ruling Afghan group’s belief that their entire eastern border artificially divided the Pashtun people, more of whom live in Pakistan than in Afghanistan, as part of a typical British divide-and-rule plot is well known.

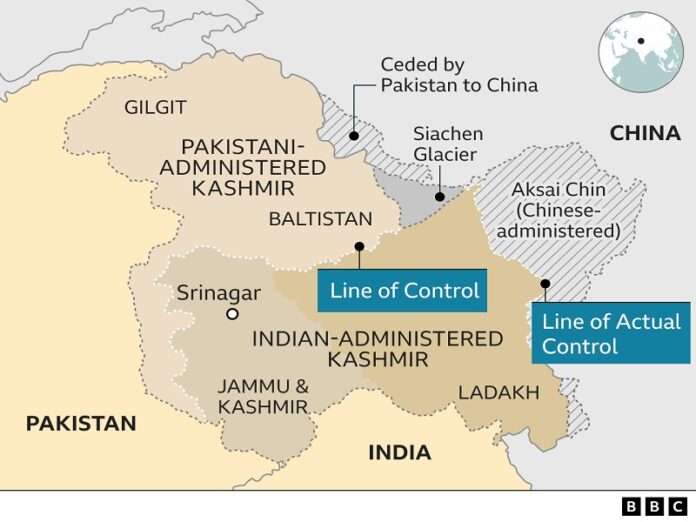

What’s novel about the abovementioned ministry’s post though is the Taliban’s recognition of J&K as separate from Pakistan. The part of that former princely state which abuts the Wakhan Corridor is claimed by India but controlled by Pakistan, yet Kabul apparently doesn’t consider it to be part of either since it referred to the region by its old name. Pakistan regards it as the administrative territory of Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) while that part of India nowadays falls under the union territory of Ladakh.

India bifurcated its region of J&K half a decade ago, with led to Pakistani-controlled GB being considered Ladakh by Delhi while the remainder of that former princely state under Indian control became the new J&K from its perspective. The Taliban’s decision to describe the Wakhan Corridor’s southeastern border as J&K instead of GB or Ladakh was therefore a purely political move which suggested ambiguity about its current status with the innuendo that a restoration of independence might be preferred.

That implied stance won’t irk Delhi though since the Taliban is now its informal partner but it’ll certainly irritate Islamabad. Those two are embroiled in a fierce security dilemma that’s responsible for Pakistan’s latest counterterrorism operation, both of which the reader can learn more about from this piece here last month. Considering their border tensions, the Taliban seemingly calculated that it would be too provocative to publicly describe the Wakhan Corridor as bordering both India and Pakistan.

This explains the real likely reason why they decided upon using the outdated name of J&K, which wasn’t to bizarrely revive a now-irrelevant debate about whether that former princely state’s independence should be restored. The purpose was to avoid provoking Pakistan’s most hawkish policymakers into contemplating a comprehensive kinetic response (i.e. cross-border campaign) if they interpreted the group’s theoretical use of the word Ladakh as supposedly proving that they’re “Indian puppets”.

Legally speaking, the Kashmir Conflict can’t be resolved until the implementation of relevant UNSC Resolutions, which India and Pakistan interpret differently. Nevertheless, those two’s partners employ each’s terminology for the parts of that erstwhile princely state under their control, with the Taliban now becoming the notable exception. Its description of the Wakhan Corridor’s southeastern border as J&K is thus clearly a political provocation against Pakistan but not severe enough to warrant a kinetic response.

The signal being sent is that the Taliban wouldn’t mind if Pakistan lost control of GB, which is meant to reaffirm just how much that group hates its former patron nowadays but possibly also to hint that its terrorist-designated TTP allies might soon spread their reach inside that region. Even if the latter have no such intentions, the Pakistani authorities might preemptively overreact through a forthcoming crackdown that provokes another genuinely grassroots protest movement that escalates into a crisis.

In other words, the Taliban’s decision to describe the Wakhan Corridor’s southeastern border as J&K instead of GB is actually a clever psychological provocation against Pakistan, albeit one which remains below the threshold of unacceptability and thus couldn’t legitimately justify a kinetic response. Islamabad is definitely irritated, but its hands are tied unless hotter heads prevail and push the country into commencing a conventional cross-border conflict over this, though that appears unlikely for now.