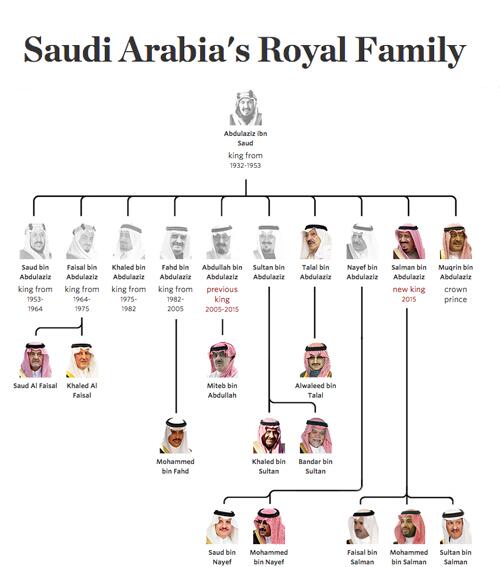

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is close to becoming king as the health of his elderly father, King Salman, deteriorates; he was recently treated for a lung infection. While Mohammed bin Salman’s succession to the throne may seem inevitable and straightforward, he will face two challenging decisions: appointing a crown prince and designating a deputy crown prince.

When appointing a future crown prince, he theoretically needs to consult Saudi Arabia’s 1992 basic law of governance, which stipulates that rulers are drawn from the male descendants of Ibn Saud, with the “most upright among them” selected for the role.

But a 2017 amendment by King Salman notes that after the sons of Ibn Saud, there should be “no king and crown prince belonging to the same branch of the founder king’s descendants.”

In practice, as king, Mohammed bin Salman would have enough power to ignore the amendment and appoint one of his brothers as crown prince – but this would not be without consequences. He would appear even more ruthless in excluding other branches of the House of Saud.

Such a move would further alienate the large pool of cousins belonging to important branches, such as al-Fahd and al-Sultan, neither of which has been humiliated like al-Nayef and al-Abdullah. So far, despite rumors about who Mohammed bin Salman may select as crown prince, the decision has been kept secret.

It is also uncertain as to whether the future monarch would follow the path of King Abdullah, who created the role of deputy crown prince in 2014 (before dying the following year), fearing a power vacuum if he and his crown prince both died within a short period of time. But the post of deputy crown prince has been vacant since 2017, the year Mohammed bin Salman ascended to the role of crown prince.

Establishing power

King Salman never appointed a deputy crown prince, for two reasons. First, the young age of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who was in his early thirties in 2017, made it unlikely that he would die any time soon and require a deputy to step in.

Second, and more importantly, King Salman would have struggled to find a suitable deputy crown prince, as he and his son antagonized several branches of al-Saud lineage, namely Nayef and Abdullah.

Former Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef received the most humiliating blow when he was sidelined after decades of holding highly sensitive and important positions in the interior ministry and intelligence services. He was put under house arrest and has since disappeared from public life.

King Abdullah’s son Mutaib, the former chief of the Saudi Arabian National Guard, was equally humiliated when he was sacked from his military role; he has also disappeared from public life following allegations of corruption.

King Salman and his son have not endeared themselves to these two branches of the royal family and their descendants. The king could still have chosen a deputy crown prince from the other remaining important branches, but he didn’t.

Perhaps King Salman wanted his own son to have time to establish his power base without the patronage of older senior princes, most of whom had held senior positions in government as ministers or military commanders.

Royal prerogatives

Over the last seven years, Mohammed bin Salman has been a solo crown prince. He effectively became the state, amassing tremendous power over every aspect of government and life in Saudi Arabia, from the military to entertainment.

Mohammed bin Salman has been an absolute ruler, listening only to his close friends, foreign advisers, consultants and coterie. His domestic and foreign policies reflect his own desires, rather than consultation with a large group of senior and more experienced princes. A deputy crown prince would have been a nuisance, to say the least.

In addition, the majority of eligible candidates for the positions of crown and deputy crown prince are still haunted by the memory of the Riyadh Ritz Carlton, which doubled as a detention center after Mohammed bin Salman launched a wide-ranging “anti-corruption” crackdown against powerful officials in 2017. He later released them after they paid billions of dollars to the state.

As future king, Mohammed bin Salman will face the challenge of appointing an eligible crown prince and a deputy, both of whom must not challenge him or appear stronger than he is due to experience, age or aura. He will have to choose less powerful and more docile princes, so that they do not undermine his authority and single-mindedness.

No doubt, Saudi society will be irrelevant to the process, as these decisions are strictly royal prerogatives. The future of the leadership is beyond a disenfranchised society that lacks pressure groups or civil organizations. Religious scholars, merchants and tribal groups will have no say in the matter; they will simply be summoned to the palace to pledge allegiance to whomever Mohammed bin Salman chooses.

This is how a repressive absolute monarchy works. It does not consult – let alone share power – with its own royals, not to mention elites and notables.