Late Sir Roger Scruton wrote tirelessly about the importance of a sense of “we” as the basis of democracy that prevents fatal political divisions. Along with the weakening of national cultural cohesion, this belonging together has been weakening in European countries. Culture war is, in this context, an issue of social order. This battle is, however, more often analyzed from the point of view of classical liberalism facing a radical ideology reminiscent of communism. I tell about this approach through Rod Dreher’s grave summary, predicting that the only options of our American stronghold of liberalism are soft totalitarianism or civil war.

Liberalism is too limited a perspective on the matter because it does not see the more important aspect of the problem, which is exactly the fleeting social order. Another American, a political theorist, Patrick Deneen, sees the doom of liberalism similarly to Dreher but tries to show that there is a new future for social order and democracy – if liberalism is transcended. He goes beyond liberalism in his books Why Liberalism Failed and Regime Change and identifies lost order as the essence of our condition. Having identified the disease, we can now search for a cure. This cure is a “mixed constitution”, an ideal of equilibrium between the interests of the “many” and the “few.” What Deneen calls common good conservatism overcomes liberalism’s commitment to globalized indifference. Instead of merely defending the freedom to pursue the good, common good conservatism promotes a society that assists ordinary fellow citizens commoners, in achieving flourishing lives. I will explain this option and ask how to promote it in the European Union.

About the inevitable course of the culture war in the US

Rod Dreher contemplated (in the Hungarian Conservative in 2021) the swift march of the woke through American institutions. Because the US development radiates to every Western country, we should be heedful of his observations and his illustrative examples from the Walt Disney Company and the US Central Intelligent Agency.

The Walt Disney Company has been institutionalizing antiwhite racial ideology by compelling its employees to affirm that the US has ’a long history of systemic racism and transphobia. Especially white employees must ’work through feelings of guilt, shame, and defensiveness to understand what is beneath them and what must be healed’. They are advised to refuse to ‘question or debate their Black colleagues’ ‘lived experience’ and regard their country as one ‘that elevates white culture over others’. Workers who object cannot become ‘antiracist’ and are thus racist by definition.

Dreher’s second example was a YouTube video produced by the Central Intelligent Agency to recruit young people. There was a clip featuring a CIA officer wearing a feminist power T-shirt, walking the halls of the agency, and discussing herself. She tells the viewer that she is a Latina, that she is ‘cisgender’, that she is intersectional, and has been diagnosed with a mental illness. But, she says, she is proud of all of this and grateful that she can be fully herself at the CIA.

Bizarre programs of race radicalism and gender ideology indoctrination are now becoming standard everywhere to the extent that anybody who objects to them risks becoming a target of contempt and personal and professional destruction.

In order to understand this new totalitarianism in the US, Dreher refers to the experiences of the survivors of previous century communism. Admitting that there is no secret police or gulags in the US today, Dreher underlines that there is, however a totalitarian system in which politics is controlled by a single ideology and everything within society is political.

Dreher observes that there was already, after Trump’s election a sense of division that justified everything and anything. Accordingly, he believes that “Americans are on the verge of a brave new world” and gives the following reasons for his opinion: “Given the decline of Christianity and the rise of radical individualism, we no longer have in America the sense of essential unity and cultural confidence that allow liberal democracy to flourish.”

Liberalism’s attraction, assumptions and anticulture

Liberalism has been able to foster individual liberty, prosperity, and relative political stability. This seems to be now over because liberalism has worn out its social and cultural foundations. It has emptied the middle ground between the individual and the state.

The liberal regime is constituted, in addition to the legal and political arrangements, by foundational anthropological assumptions – individualism with a voluntarist conception of choice. This was a profound departure from previous ancient and Christian notions of freedom. The primary goals of political philosophy in ancient Greece and Rome were the defense and realization of libertas and self-government, which was regarded as a continuity from the individual to the polity. Liberty was thus thought to involve both training in self-limitation of desires, and social and political arrangements supporting the virtues of temperance, wisdom, moderation, and justice.

Liberalism instead based politics upon the idea of the autonomous choice of nonrelational separate individuals. The legitimacy of all human relationships, family relationships included, becomes dependent on whether they have been chosen on the basis of self-interest.

Liberalism saw itself as a mere description of our decision, but in fact it educates people to think differently about themselves. People are taught to hedge commitments, to see relationships to place, neighborhood, nation, family, and religion as exchangeable.

The dual expansion of the state and personal autonomy rests on the gradual loss of particular cultures, and their replacement by a pervasive anticulture, where time is a pastless present, and a relationship to place exchangeable and without definitional meaning.

This void of shared cultural content and irreligion invites to be filled with anything which helps in encountering increasing worldly evil. René Girard wrote how the western concern for victims, a fruit of Christian culture, is changing into something monstrous: “The current process of spiritual demagoguery and rhetorical overkill has transformed the concern for victims into a totalitarian command and a permanent inquisition.” The nightmare of wokism gets deeper and deeper.

Culture war from the point of view of order

Patrick Deneen teaches us to see the culture war as a phenomenon that arises from anticulture and the inevitable loss of social order. An example of this is the trajectory of transgenderism. Formerly, the fact that the overwhelming majority of humans are either male or female was a part of our taken-for-granted order. To misidentify one’s gender was medically described as a disorder. Transgenderism denies this, disputing thus a fundamental order in the world. It imposes disorder by accusing the defender of this order of a crime.

In general denying our common sense alienates us from our shared culture. Expressing freely means expressing in a relaxed, intimate, “between ourselves” way, as an aspect of intuitive belonging. “Wokism”, “me too”, critical race theory etc is totalitarian because it dismantles those cultural spaces in which people are able to associate freely and spontaneously and which Georg Orwell praised as free of the state and officialdom (Waterfield: Why Orwell matters, spiked 2022).

But this is how liberalism works. It sets inevitably the experience and preferences of an individual above community and its customs. Its program and logic is that you become yourself by transgressing norms and boundaries.

The woman we met with in CIA YouTube video declared her gender by using the term ‘cis-gender’ as a choice and not the fate she was born into.

Liberals ignore the problem of order and approach the culture war as a continuation of the age-old conflict between liberty and authoritarianism. They defend open discussion and free speech against those who argue that the experience of “oppressed” victims must not be questioned.

From the point of view of order, defending freedom in culture war actually pushes disorder forward, as Deneen writes: “Merely to claim the right not to use someone’s preferred pronoun is to concede that one’s pronoun is a matter of opinion, and that liberty demands that people can think about gender, sexuality, marriage, and family in whatever way they like.”

Also contemporary conservatism, as if still fighting against communism “Lacking any other vocabulary, [it] resorts to the hackneyed assumption that every problem can be understood through the dichotomy liberty vs. oppression.” In Deneen’s words: “Well-engrained habits lead to the brain-dead conclusion that what we face today is a renewal of communist oppression.” From this angle threatening instances, such as efforts to silence campus speakers, are seen as a renewed marxism, totalitarian impingement on our freedoms. (Deneen: In Defense of Order – Part 1 The Priority of Order over Liberty 1.9. [substack channel: Postliberal order])

Our moment in history has fundamentally changed. Lack of freedom has been replaced by disorder as our major problem, but our political framework and principles of action are still the same. Disorder reigns as our political world pits the Party of Disorder (Left) against the Party of Freedom (Right).

Regime change, “mixed constitution,” and the common good

Deneen suggests a new kind of regime, a “mixed constitution”, a more harmonious relationship between the “many” and the “few”, the people and the elite, which can avoid civil war and totalitarianism.

Liberalism embraced the enlightenment faith in progress. Separating the progressed from the recidivist became an essential feature of the modern liberal regime. A fundamental division was introduced into society: those on the side of progress and those who stand against the faith in a better future.

Reflecting our political division, the ideology of progress asserts that time is divided between an era of darkness and light. Thus past, present, and future are separated, which fosters a dismissiveness toward the past, discontent with the present and optimism toward the future.

Instead, we should have an integration of time, emphasizing memory toward past, gratitude in the present, and a cautiousness toward a too optimistic view of the future. In Deneen’s words: “Our capacity to deliberate together over less obvious but often severe costs of changes (…) would result from the integration of time. Only through such integration can there in fact be a political community (…).” This means a nation, including “those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born”.

The aspiration of liberal “globalism” is to promote universalism based on the ethos of effectual indifference. There is no objective “good” to which humans can agree, but every individual should pursue his or her idea of individual good.

Culture war can be seen as an effort to refound the societal and even metaphysical order on the basis of individual preference and eliminate every last vestige of any claim to an objective good. The devotion of liberal political order demands that those who resist this commitment to individual preference must be forced to conform.

Liberalism’s theological foundations, the dignity of every human life and the supreme value of liberty as a choice for what is good, were originally christian. Liberalism’s logic, based on the complete liberation of the individual from any limiting claims of an objective good, becomes the opposite. Liberty is defined not as self-government, but as a liberation from constraint to do as I wish.

In practice the result is a deeply destabilizing outcome of winners and losers.

The only genuine alternative to liberalism’s world of indifference is common-good conservatism as an aspiration to move beyond the failed project of liberalism. It must embrace a new effort to articulate and foster a common good, “common” meaning both shared and ordinary.

Common good consists in those needs and concerns that are identified in the everyday requirements of ordinary people. In a good society, the goods that are “common” are reinforced by the habits and practices of ordinary people, forming the common culture. If it is weakened or destroyed, a responsible governing class should renew it. So the fortifying forms of family, community, church, and a cultural inheritance are a “political problem” in need of political redress. Our condition after liberalism requires a governing ideal of mixed constitution, enabling the common-good conservatism, and thus common good, common sense, and a shared culture.

How do we get there?

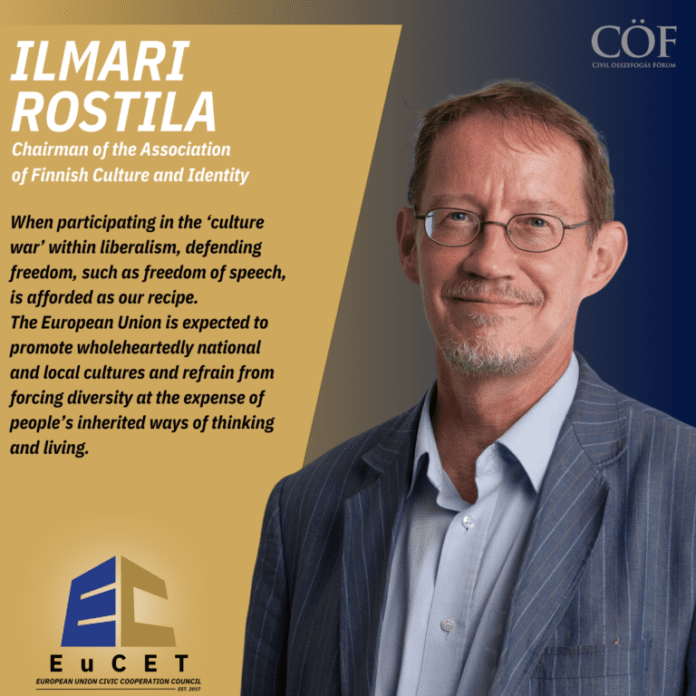

Dr. Ilmari Rostila

Chairperson of the Association of Finnish Culture and Identity