Authored by Mike Shedlock via MishTalk.com,

When bureaucrats put their personal agenda ahead of what science can deliver, bad things happen…

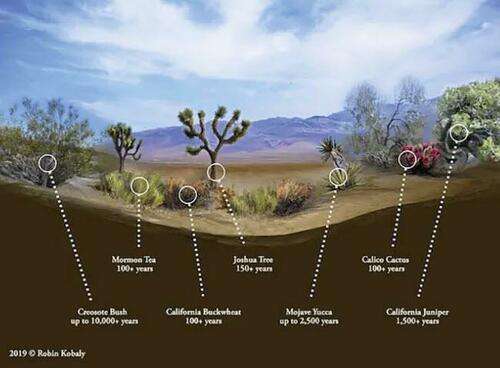

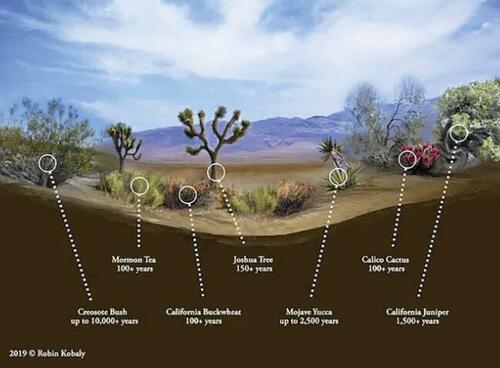

The desert isn’t barren, 90% of the story is underground.

A Costly Omission in Planning for Climate Change

Please consider A Costly Omission in Planning for Climate Change by Robin Kobaly, a twenty-year career as a botanist with the BLM, with a Master’s Degree in biology.

Most people are not aware of the vast amount of carbon that is captured and stored underground in desert soils.

Desert plants store much of their captured carbon deep underground in a massive network of connected roots and fungal root-partners, unlike forests which store most of their carbon aboveground or near the soil surface. Historically, much of the desert’s “soil organic carbon” has been missed by soil scientists, because many soil studies conclude at “plow-line depth,” or between 6 and 12 inches.

As with other desert plants, the long, water-seeking roots of the California Evening Primrose partner with miles of mycorrhizal filaments, and together they store large amounts of carbon underground.

Because there can be so many miles of fungal hyphae (covered with glomalin) in each cubic foot of desert soil, glomalin is attributed with storing one-third of the world’s soil carbon.

Much of the carbon these plants capture aboveground from the air and convert into sugar is eventually turned into inorganic carbon underground. When the long roots breathe out carbon dioxide deep into dark moist soil, this carbon dioxide combines with the abundant calcium in our arid soils to create mineralized deposits called caliche (calcium carbonate). These deposits start as tiny crystals but eventually grow to large crystals, then chunks, and into layers of caliche that can start at the surface or form at various depths underground. These caliche deposits can store captured carbon in this inorganic form for hundreds, to thousands, to even hundreds of thousands of years . . . if not disturbed.

Dr. Michael Allen at the UCR Center for Conservation Biology commented on the desert’s capacity to store large amounts of carbon dioxide as caliche, noting that “The amount of carbon in caliche, when accounted globally, may be equal to the entire amount of carbon as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.” Despite its long-term storage capacity, caliche releases its sequestered carbon when vegetation is removed and soils are disturbed and exposed to erosion. As caliche degrades in disturbed soils, its calcium and carbon molecules are uncoupled, releasing the carbon to again reenter the atmosphere.

We might first look at Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera), an ancient, extremely slow-growing plant that is very common across both the Mojave and Colorado Deserts, and that has been found to reach ages of 2000+ years. We could calculate how much carbon one plant captures each year, then extrapolate how much carbon an individual yucca plant would sequester in say, a 1000-year lifespan. Then figure how many Mojave yuccas are expected to be ripped from the ground in a typical industrial solar field such as the newly-approved 5,000-acre Yellow Pine Solar Project in the Mojave Desert (Pahrump, Nevada) – in this case, over 80,000 Mojave yuccas will meet their demise during the construction of an array expected to operate for perhaps twenty years before becoming obsolete. Will the reduction in carbon that would have been sequestered (and stored underground) by those 80,000 Mojave yuccas actually be offset by possibly twenty years of the solar project that replaced them?

If we could do the same for the creosote bush that also can live for thousands of years, we might gain still more perspective on the critical question of net carbon gain or loss through various management practices in our ancient desert landscapes.

If few people realize the intrinsic value of the desert’s carbon contributions, it becomes more difficult to protest when thousands and thousands of acres of desert habitat are scraped bare for solar fields. It appears that the California Deserts may be sacrificed to meet California’s climate goals without even considering the full consequences of doing so. Where will our carbon footprints lead us . . . down a path that leads to a slashed-apart, industrialized desert where throngs of people once flocked for solitude and for vast uninterrupted vistas of an ancient landscape? Let’s not lose this treasure when there is a smarter path forward, including solar panels on rooftops, parking lots, fallowed agricultural lands, and even exposed aqueducts.

An Oasis Has Become a Dead Sea

The Guardian comments Solar Farms Took Over the California Desert: ‘An Oasis Has Become a Dead Sea’

Over the last few years, this swathe of desert has been steadily carpeted with one of the world’s largest concentrations of solar power plants, forming a sprawling photovoltaic sea. On the ground, the scale is almost incomprehensible. The Riverside East Solar Energy Zone – the ground zero of California’s solar energy boom – stretches for 150,000 acres, making it 10 times the size of Manhattan.

Residents have watched ruefully for years as solar plants crept over the horizon, bringing noise and pollution that’s eroding a way of life in their desert refuge.

“We feel like we’ve been sacrificed,” says Mark Carrington, who, like Sneddon, lives in the Lake Tamarisk resort, a community for over-55s near Desert Center, which is increasingly surrounded by solar farms. “We’re a senior community, and half of us now have breathing difficulties because of all the dust churned up by the construction. I moved here for the clean air, but some days I have to go outside wearing goggles. What was an oasis has become a little island in a dead solar sea.”

Concerns have intensified following the recent news of a project, called Easley, that would see the panels come just 200 metres from their backyards. Residents claim that excessive water use by solar plants has contributed to the drying up of two local wells, while their property values have been hit hard, with several now struggling to sell their homes.

The mostly flat expanse south-east of Joshua Tree national park was originally identified as a prime site for industrial-scale solar power under the Obama administration, which fast-tracked the first project, Desert Sunlight, in 2011. It was the largest solar plant in the world at the time of completion, in 2015, covering an area of almost 4,000 acres, and it opened the floodgates for more. Since then, 15 projects have been completed or are under construction, with momentous mythological names like Athos and Oberon. Ultimately, if built to full capacity, this shimmering patchwork quilt could generate 24 gigawatts, enough energy to power 7m homes.

Kevin Emmerich worked for the National Park Service for over 20 years before setting up Basin & Range Watch in 2008, a non-profit that campaigns to conserve desert life. He says solar plants create myriad environmental problems, including habitat destruction and “lethal death traps” for birds, which dive at the panels, mistaking them for water.

He says one project bulldozed 600 acres of designated critical habitat for the endangered desert tortoise, while populations of Mojave fringe-toed lizards and bighorn sheep have also been afflicted. “We’re trying to solve one environmental problem by creating so many others.”

Much of the critical habitat in question is dry wash woodland, made up of “microphyll” shrubs and trees like palo verde, ironwood, catclaw and honey mesquite, which grow in a network of green veins across the desert. But, compared with old-growth forests of giant redwoods, or expanses of venerable Joshua trees, the significance of these small desert shrubs can be hard for the untrained eye to appreciate. “When people look across the desert, they just see scrubby little plants that look dead half the time,” says Robin Kobaly, a botanist who worked at the BLM for over 20 years as a wildlife biologist before founding the Summertree Institute, an environmental education non-profit. “But they are missing 90% of the story – which is underground. ”Her book, The Desert Underground, features illustrated cross-sections that reveal the hidden universe of roots extended up to 150ft below the surface, supported by branching networks of fungal mycelium. “This is how we need to look at the desert,” she says, turning a diagram from her book upside-down. “It’s an underground forest – just as majestic and important as a giant redwood forest, but we can’t see it.”

For Alfredo Acosta Figueroa, the unstoppable march of desert solar represents an existential threat of a different kind. As a descendant of the Chemehuevi and Yaqui nations, he has watched as what he says are numerous sacred Indigenous sites have been bulldozed.

“There are so many other places we should be putting solar,” says Clarke, of the National Parks Conservation Association, from homes to warehouses to parking lots and industrial zones. He describes the current model of large-scale, centralized power generation, hundreds of miles from where the power is actually needed, as “a 20th-century business plan for a 21st-century problem”.

Lose-Lose Policy

Experts suggest the mad rush to convert desert to subsidized solar panels may be releasing mass amounts of stored carbon while simultaneously destroying archeological sites in the process.

Battles Rage Over Biden’s Clean Energy Projects as the Size and Cost Jump

Meanwhile, back East, Battles Rage Over Biden’s Clean Energy Projects as the Size and Cost Jump

Also note, The Inflation Reduction Act Price Jumps From $385 Billion to Over $1 Trillion

What to Expect When Politicians Try to Pick Technology Winners Part 1

On may 25, with a spotlight on the EU, I commented on What to Expect When Politicians Try to Pick Technology Winners Part 1

This was part 2.

Biden is so clearly wrong, even the extremely liberal Guardian sees it. But it’s full speed ahead with massive subsidies for something counterproductive for the goal.